Part I of III—Where we are and how we got here.

Social Media is a distorted reflection of us, and it’s time to lens correct.

It’s easy to blame social media giants for confining us to bubbles, polarizing our perspectives, and letting bots run rampant as we fear censorship of free thought. It’s harder to take a look at ourselves or ask eloquently for change.

Many* have attempted to write about these dire potentialities since the onset of the web, but their valiant efforts have hardly held back the stratospheric rise of social networks or reinformed the misguided way we use them.

Social networking started out as a genuine and novel way to connect us. We smiled mostly as we watched user numbers skyrocket and spent more time online, but the vast ways social media changed us has been almost imperceptible.

Two decades of watching my relationships digitize (while the dream of a humane realtime web failed to materialize) have led me to a new understanding.

The blame cannot possibly rest on a single executive or solely on the pernicious algorithms that do most of the dirty work for the platforms they serve.

Remedying the ugly landscape of social networking depends on all of us.

This is Part I in a three-part series dedicated to understanding where we’re at with social media platforms, the problems and potential they embody, with a discussion around solutions that may best serve us as a society.

From Where We Stand

As of 2020, over half of the planet uses social media.

Newsfeeds & digital inputs are informing perceptions of reality for the better part of our waking lives. Prior to COVID19, we spent over 2 hours per day on social networking apps, and that number has grown substantially for consumers in quarantine according to Global Web Index.

3.9 Billion out of the 7.8 Billion of us are, “connected”.

It’s not just about the time we spend on social media platforms, it’s the way they dominate our capacity to make sense of the world, day by day. We wake up to the alarm of our smartphones, grab them each morning, and fall victim to the notifications of the day before our first mindful breath.

Americans now check their phones 96 times a day — that’s once every 10 minutes, according to a study performed at the end of 2019* by Asurion.

*The data that informed this study was from 2017.

Every notification a chance to hype up our neurochemical production for reward chemicals like dopamine (likes & comments), connection chemicals like oxytocin (follows, emails, and group connection), well-being chemicals of creative expression like serotonin (when we finally act or share)—but more often than not, we’re reminded of the lack thereof.

This misplay of neurochemicals is why we simply don’t feel as good as we hope. Why? The way we live is decidedly different than it used to be, and it’s many thanks to a reliance on social media that we don’t fully understand.

Our only method of connection

In an increasingly physically isolated world, this works both for us and against us, we deal doubly with indecision. Is what we actually do worth sharing? Does that consideration need to follow us wherever we go? Is the walk we take, the photo snap we grab, or the meaningful cause we contribute to worth a post on Instagram for a few likes? Are we to trust the, “like” method of value contribution at all? We’ve watched the nature of connectivity trend towards shallower interactions, even as the bitrates and fidelity of content increase.

A single phone call to a trusted family member or friend is still worth more than a day of baited-breath waiting for a dating app match, a Snapchat reply, or a slew of digital hearts or likes on the platform of your choice.

Ask yourself how present you are when you press, “like” yourself. What are you really providing to a contact of yours and what (that’s real) are you actually holding back?

Each notification we let alert us is a gamble that breaks our flow, our productivity, and puts our sense of well-being on the line. Like casino gambling, the odds are stacked against us, with the most likes and attention going to the influential few. Natural law flouted, still we play the game. There is no reasonable alternative, and the withdrawal symptoms feel so much worse than silence.

It’s no secret our world has been teetering on statistics of rising depression, anxiety, and suicide rates — much due to a lack of true connection among us. As COVID19 normalizes even more time spent online, we must work to ensure the online social space is not one that exacerbates our feelings of isolation or discord.

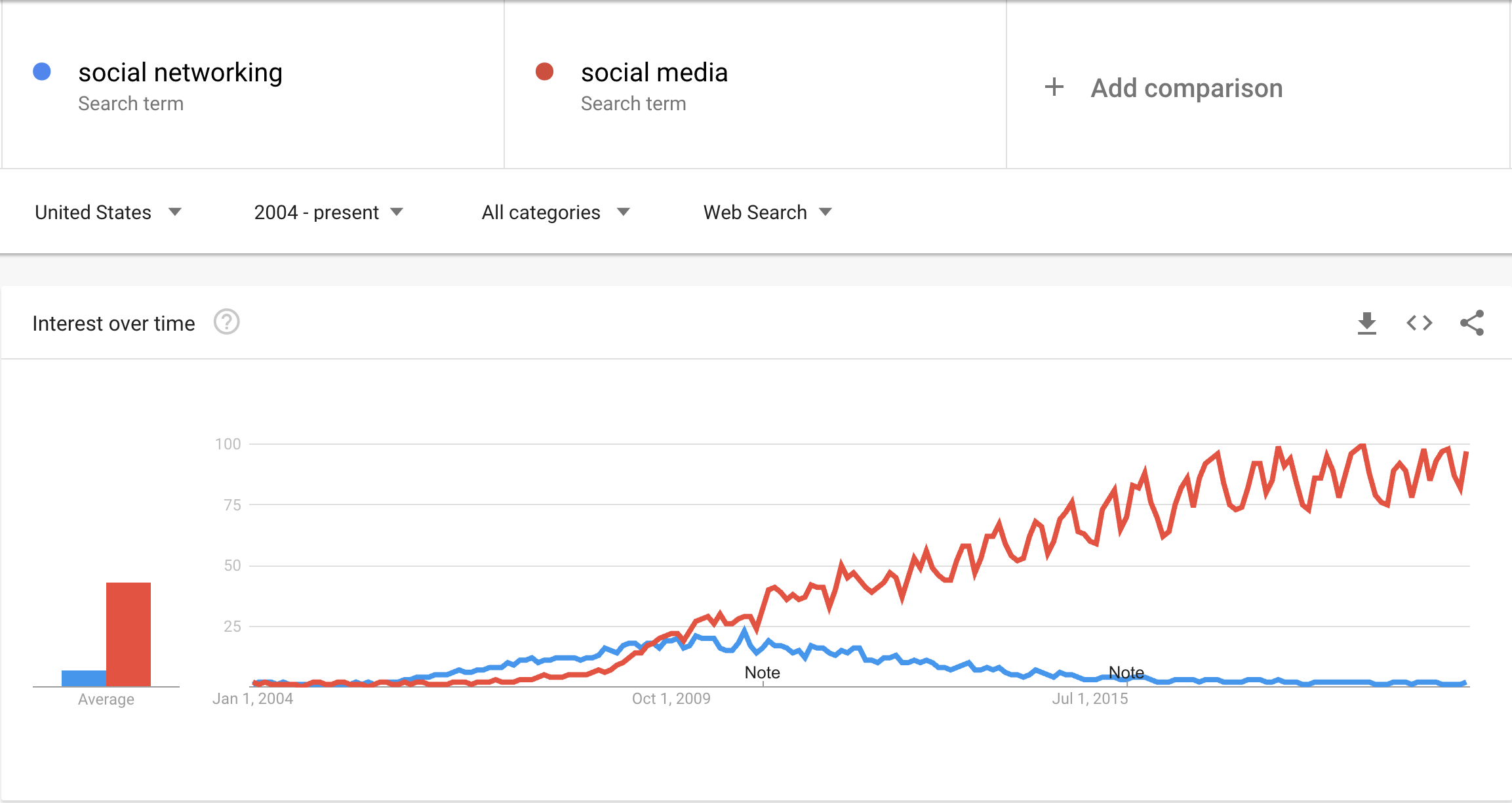

Google Trends illustrates search volume relative to peaks over time. Searches for, “depression” (in red) were near all-time-highs when metric tracking became available to the public. 2010 marked the year searches for, “anxiety” and “social media” began to rise in tandem. Perhaps the false requirement of supporting a persona on social media outside of our true, “selves” has brought with it the added anchor of anxiety we see here. The correlation above is presented for illustrative purposes only and makes no scientific claims.

“If our reality is informed by what we spend time perceiving, it’s well past time to admit the digital world has officially taken the number one place of influence over our minds.”

What’s Truly at Stake?

As the #stophateforprofit movement calls out, the lens social media places on our perceptions can be polarizing, distracting, confusing & straight up illusory.

The Great Hack documentary showed us that our perceptions can be bought and sold. The unspoken narrative is how fully we have allowed our own behaviors to change, and how durable these behaviors have become.

We have not only outsourced our meaning-making and opinions to news feeds, we’ve also handed over the sovereignty of our own emotions. What we’re exposed to online and how our own content is received by peers may inform how we feel to a greater extent than our lived experiences. Meanwhile, we’re almost powerless to admit this to our own networks of friends, who are likely suffering from unproclaimed feelings, too.

Part of the blame can be placed on our own lack of feed curation, screentime discipline, and cognitive biases, but we cannot simply blame ourselves. As we understand they’ve been built to capture our attention, take advantage of our psychological weak points, and profit from our own vulnerability, we must hold platforms accountable, too.

For a deeper look into the dark side of social media, be sure to check out, “The Social Dilemma” on Netflix which by its own description, “explores the dangerous human impact of social networking, with tech experts sounding the alarm on their own creations.” It’s not actually as dark as it seems if you're able to take in what they share. Their goal is not to get you to quit social media as much as it is to start a conversation, a goal I share in similitude with this blog series.

Yes, we live in a simulation.

If our reality is informed by what we spend time perceiving, it’s well past time to admit the digital world has officially taken the number one place of influence. This is no longer a casual problem, but one of massive importance. The digital world is the lens through which we make consequential decisions about the real one. It is so integrated into our daily lives we can hardly trust ourselves to act or reason with any sense of digitally-detached sovereignty.

More groups of people believe they are correct in their digitally partial views than could possibly be represented by actual truths. Meanwhile, our attention is pulled away from global-scale problems and emerging social causes that require both our time, energy, and collaboration.

As Tristan Harris said in, “The Social Dilemma” “If we cannot agree on what is true, or that there is such a thing as truth, then we are toast. This is the problem beneath other problems, because if we can’t agree on what is true, then we can’t navigate out of any of our problems.”

The Elephants in the Room: Bots, Fake News, Censorship, and Free Speech.

As if our own differences of (manipulated) opinion weren’t enough, we’ve also got the above mind-wrenching topics to deal with. Some estimates place the number of non-human social media accounts between 5% and 15% of all active users across platforms. This in itself may not seem alarming until you pair it with the fact that in acute situations, an even higher amount of content around emerging current events can be traced back to bot accounts.

For the cherry on top, a recent study showed the average human has only a 70% chance of identifying whether an advanced bot intelligence is human or not. In the heat of the moment, with presumably breaking news surfacing, I can’t help but presume that number is substantially lower.

In a world where everyone knows what, “Fake News” is, it may be disarming to realize that it actually spreads 6 times faster than the real thing. The bots that spread it are getting better and better at that too, so it will likely get worse. It must be mentioned that the real reason fake news spreads faster than truth is that actual humans are being duped. When strong emotional responses like surprise and disgust are at work, we’re the ones doing the spreading of falsities. We’re the ones skipping the crucial steps of critical thinking, consideration, and research.

We mindlessly retweet and share stories with reactive headlines as our egos consider the potential of having uncovered something that matters, first. The meta-problem here is that our own activity is starting to mirror what these bots are programmed to do themselves, and truth becomes playfully harder to find.

It’s no wonder groups are calling out social media platforms to step up their management of fake news, hate groups, and misinformation. These types of content have the power to polarize conversations, incite riots, and change the outcomes of elections.

The muddy water in-between is the difference between censorship and free speech, and whether it’s privately controlled or governmentally dictated. I’ve never met anyone who’s loved the idea of censorship on the internet, yet if we can’t trust platforms to manage this on their own, the government will certainly step in.

If the blame of fake news, bots, and discriminatory polarization lands unilaterally on social media platforms, we risk mutiny of our own vehicles for open, real-time connectivity. It’s hard to expect the government itself to come up with a fair solution, just as it is hard to assume the social platforms themselves will properly police. After all, whether we’re one of Facebook's 45,000 human employees or a presumably smaller governmental task force; we’re just humans, limited to our own best understandings and options to take action.

Both Republican and Democratic forces alike would love to limit section 230 of the communications decency act, which essentially has allowed for the free and open internet as we know it. What section 230 does is prevent large tech companies or publishers from being liable from the content their own users publish. If it’s adjusted or repealed, the social media platforms as we know them would be greatly hampered and different from how we know them now. We could see bans on realtime streaming, we could see forced reviews of content posted, and our connectivity as humans in isolation during a pandemic may vastly decrease.

As, The Hill revealed, “On Sept. 1, Facebook announced that section 3.2 of its ToS would be amended to include that they can “remove or restrict access to your content, services or information if we determine that doing so is reasonably necessary to avoid or mitigate adverse legal or regulatory impacts to Facebook.”

It’s easy to get your mind in a place of conspiratorial thinking when this is laid out for you in simple English. Remember most politicians are looking for whatever edge they can get for a vote, and most for-profit companies are looking to stay profitable. Each of these motivations could well change society for the worse, and it’s up to us to stay alert.

What we’re seeing now is two entities shoring up for battle over a psychological landscape they don’t rightly own. If this does scare you as it perhaps should, it’s all the more reason to understand the potentials here and participate as you can. Remember these laws and ramifications only exist because our own individual behaviors and biases cannot be trusted. We can all do better.

So How Did We Get Here?

If more of us recognize the history of social networks and understand they are now powerful enough to shape our perceptions and behaviors, perhaps we may all ease away from our dependence on them as we work out the kinks.

The Birth of A Giant

In the fall of 2004, I arrived at the University of Michigan and found myself amongst a novel landscape of latent social connections. Around 40,000 bright young people from the corners of the earth, gathered in one place to learn, socialize & define our futures together.

My classmates and I (along with an exclusive group of the nation’s top 25 universities) had been invited to join Facebook the summer before fall semester, and I remember the excitement of it all. There was no need to fawn over the classmate crushes left behind in my physical high school yearbook, I had access to peruse the entire incoming class of college freshman!

I made about 150, “friends” on Facebook that summer, and even met a few in person when I got to campus. We used Facebook for connecting with people sharing similar interests, keeping up with campus activities, and creepily checking out potential dates before actually meeting up. Of course, barring the last detail, that’s what you did by physically attending college prior to 2004.

“In 2006, when Facebook had less than 10 million members, almost 10% of the (mostly student) userbase joined a group contesting the introduction of the news feed itself.”

An Early Identity Crisis

Social networking is just a tool, I thought. By the second semester, most classmates agreed, we just weren’t sure what kind of tool it was. Facebook was an unregulated dating service, rudimentary group message board, basic personal homepage, and event planner. We hoped Facebook (and the social web at large) would evolve into a more meaningful experience; but even in 2004, we worried it was taking time away from the usual spontaneity of being a college student. I don’t think it actually helped foster many relationships either. The worst lines you could hear at a party were, “I think I’ve seen you on Facebook.” That was a pretty quick recipe for being ghosted for good.

There was just something so unnatural about having access to the personal lives, photos, and activities of complete strangers. At the same time we were helplessly drawn to this access, and as it turns out, so were investors and data brokers alike. Facebook slowly coaxed us into the normalization of these behaviors. Sharing our real names online, uploading photos of ourselves, and allowing our content & data to be commoditized and sold — these were all firsts. Our relinquishment of these seemingly simple boundaries of privacy has made tech investors billions of dollars while changing the entire landscape of civil discourse, commerce, and human connectivity.

My millennial generation welcomed and ushered in the era of digital connection under the impression we’d use these tools to shape society for the better. We did worse than stand by and watch idly as these platforms stratified our sense of being & ability to make sense of the world; we willingly participated and let these tools shape us instead.

Whether or not Facebook was founded on solid principles, a copy of something else, or simply an experiment in a new way technology could connect us, it was clear it was going to be monumental. The early users of Facebook were both excited and deeply afraid. We cheered our generational cohort of inventors as they shirked governmental regulations and buyout offers. Simultaneously, we feared the power they were creating should it fall into the wrong hands — become something we never asked for, or worse—both.

The Mobile Revolution Fans the Flames

In 2006, Facebook was made available to anyone over the age of 13. The next year, the first iPhone launched and you could take Facebook with you wherever you went. The vectors of broadband access, smartphone proliferation, and unbridled social networking iteration open to the masses had met at an inflection point.

As a College Junior, I spent many nights with my good friend Brett analyzing what this growing social network and access to technology was doing to the next generation. The potential of realtime connectivity with all of humankind was a lush concept that came that invoked the feelings of a “new car smell”. The haphazard launch trajectory smelt more like a burnt-out modem.

Brett and I sensed the strangeness in the air as our peers fell victim to an unhealthy relationship with technology and our elders were helpless to understand and guide. We actually planned to write a book titled, “The Changing Face of Social Networking” which was to be a guide for parents to make sense (or non-sense) of the digitalization of human connection.

Alas, the distractions of earning a college degree, socializing, and learning about ourselves as emerging adults kept us from getting anywhere near publishing, much less a first draft. Surely our own fixation on the technology couldn’t have helped productivity to document it, but, with a psych degree and a career in tech, I haven’t stopped being a student of its effects. I chose the title of this series to honor my friend Brett’s memory, and I do hope it adds some perspective.

As the platform, “evolved”, early adopters grew out of love but the rising audience numbers kept even its haters around. For every dissatisfied user who warned of their intention to quit, another 100 new users happily signed on.

“It was the point at which social networking (user-directed) became social media (platform-directed), and users have slowly given up our power ever since.”

As the above chart shows, many of the popular platforms we use on a daily basis grew extremely fast, leaving little time for consideration of their true lasting impacts on our society. The platforms endlessly iterated towards profitability at the expense of our privacy, our self-control, and our attention spans.

We could chalk the above statement up to a lesson for us as individuals to work on our time-management, but it’s difficult to take full blame when our requests as users or even watchdog groups have been historically ignored. The warning signs have been around for years, but we’ve ignored them; giving the platforms the ability to effectively ignore us.

Early signs of impertinence & userbase disregard.

In 2006, when Facebook had less than 10 million members, almost 10% of the (mostly student) userbase joined a group contesting the introduction of the news feed itself. I remember personally joining the “Students Against Facebook News Feed” group, which peaked at over 740,000 members in 2006.[Wikipedia]

The idea that Facebook would harvest & repurpose our data/content and start to resemble any sort of broadcast or content aggregator was disheartening. Everyone thought it was creepy, but one way or another, we all acquiesced. We were told we had been heard, a few tweaks to the privacy policy were made, and the newsfeed came anyways. To match this effort in terms of today’s userbase numbers, we would need 200 million people to sign a petition to change Facebook. Still, it would be no guarantee of change, unless we find ourselves in an environment riper for it.

The news feed was the first step towards social media becoming the attention hoarding behemoth it is today, and we were powerless to stop it. As it became widely adopted in 2009, this marked a point at which social networking (user-directed) became social media (platform-directed), and users have slowly given up our power ever since.

It was a necessary step in the transition from limited cable TV access & perspectives towards democratized internet access. We became freer than ever before to make our own choices about content and expression. At the same time, we went from Nielson ratings to a free for all and the powers that be have picked up the slack as individual users have let go of the reins.

Inaction is Action

Sure, we signed petitions against platform changes we didn’t like. We tried to build open-source versions with private data ownership & transparency, but we stayed with the crowd. Later, we, “jumped ship” to newer, fresher options like Snapchat and Instagram and now TikTok when our parents tried to join in on the fun. In the end, the power of technological scalability and capitalistic tendencies were too much for our idealistic expectations. Instagram sold out, Snapchat was copied, and every one of the companies competing grew exponentially regardless. I myself bet on FB stock options ahead of earnings for a few years straight and the music-tech company I’ve helped build has Facebook ads targeting to thank for much of our success.

Every few years a news story comes out about Millennials or Gen Zers leaving the platform in droves, but the truth is most of us still have profiles. If we’re not actively posting, we’re still running ad campaigns, watching videos, and wishing each other happy birthday on days (thanks to Facebook) we no longer remember.

At the same time, social media platforms provide us the lightest and most fluid ways to share information and activate meaningful social changes and innovation than ever before. Used in the right way, social media has the potential to connect all of us while providing gauges on what’s happening in our part of the world as we work to balance out solutions to our world’s rising problems.

With COVID19, we’ve lost the common denominator of connecting through in-person live events like spectator sports, concerts, and block parties. In their void, we must avoid succumbing to transitory fears and open up to the possible innovation that is now available.

The Call to Action

We deserve a better toolset of making sense of the world efficiently, in realtime, and without bias. This is not a new problem, but an initial problem of the internet that hasn’t been solved yet. If the platforms we give our attention and dollars to cannot adapt, then we must look to build anew.

As individuals, we must take an honest look at the flawed way we’re using flawed platforms and identify what improvement looks like. We must find a way to communicate with both platforms and the government to get across the best ideas of how we can work for each other.

The difficult thing about changing the way something is done—is that the longer it’s been a part of history, the deeper the history that must be understood to course-correct. My generation is among the last to have experienced life before social media took over, and if we remain silent now, this adaptive part of history may never be written.

All technological development is an ongoing experiment, and it’s up to us to call out the ways it’s failing in order to visualize a better way. Not because we hate it, but because we love it.

Part II will follow up with a breakdown of the true underlying issues of social media. It will be an attempt to define the problems with platform and self that have become almost too complex to name, as well as a synopsis of the great connective potential of what we have built.

Please follow to be notified of the next article in this series. I appreciate a clap or two to reinforce my own efforts to write. If this article has sparked thoughts of your own, please share them in the comments. I thank you for reading.

-Matt